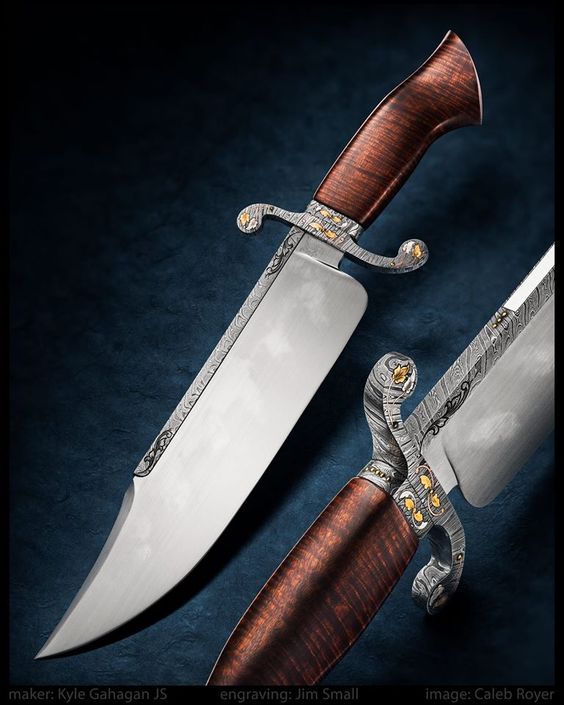

Is a U.S. Army Ranger made or is he born? Is it the training he receives that makes him a Ranger, or is there some innate quality in him that draws him to Ranger training in the first place? If you tell former U.S. Army Ranger Sergeant Kyle Gahagan (pronounced guh-HAY-gan) that he doesn’t have the proper credentials for full-time employment with your company, he’ll proceed to acquire three doctorates. If you were to suggest that he not go to work at the auto-body shop if the pain in his right arm is so bad that he cannot hold a toothbrush, he’ll go anyway and tape a hammer to his forearm. If you crush his 10-year-old spirit by telling him that the knife he spent hours making is no good and throwing it on the ground, he will one day use that craft to not only heal himself from the emotional ravages of war, but to help heal other veterans as well. Never tell an Army Ranger he cannot make a knife.

Kyle doesn’t remember a time when he didn’t want to be a soldier. As a boy, he would dress the part and play army for hours. He came from a military family with a grandfather who served in the U.S. Navy during World War II and a father who retired as a full Colonel after a near-three-decade career in the Army’s Armor branch. Kyle was born in Colorado and lived in Kentucky and Germany, but from ages 8 to 11 the family lived in Savannah, Georgia. He would see the then-black-bereted Rangers of the 1st Ranger Battalion, who were stationed at Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah, and he knew that’s what he wanted to be. “I thought they were the coolest guys on the whole planet,” he said.

Kyle got his first knife from his maternal grandfather when he was 5. It was a little Old Timer pocketknife to go with the shotgun he got for deer hunting. “I hunted with my grandfather until he couldn’t hunt anymore,” he said. His father transferred back to German, so Kyle saw him infrequently. It was his grandfather who spent time with the hyperactive boy, teaching him how to hunt and build things, how to work with his hands. At 10 his grandfather handed him a piece of aluminum and told him to go make something with it. It was his first attempt at making a knife. Although not an easy material to be cutting and grinding on, he crafted something resembling a knife. There was no heat treating involved, he said with a rare chuckle.

As Kyle learned more, he once spent a long time forging a knife. He hammered painstakingly to forge-weld steel for the blade. He made a wooden sheath, carefully lining up the wood grain. “I was so proud of that knife,” he said. He took it to an area knifemaker. That maker couldn’t stop telling him how bad it was. He threw it on the ground. “It crushed me,” Kyle said. “I didn’t make another knife for about 20 years.” He didn’t even tell his grandfather what had happened. “I think he thought I just grew out of my interest in it.”

In 1999 at the age of 19, Kyle enlisted in the Army with a Ranger contract. He was engaged when he went in and was married in between basic training and Airborne school. He went into the Ranger Indoctrination Program and Ranger school and was assigned to his boyhood heroes’ unit, 1st Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. But then 9/11 hit and he was being deployed back to back. He did two deployments in Afghanistan and two in Iraq, but because they blend into what amounted to nearly three years of being gone, he can’t quite recall the order. He was a SAW gunner in Afghanistan, he led a team for a while, and in Iraq, he was an S3, which organized training operations in the rear and coordinated missions during combat.

During one training session, Kyle was giving a private a block of instruction on the M203 grenade launcher. It hit a buried mortar not 15 meters away. They were able to determine that the grenade had not had sufficient time to arm itself, so the mine had caused most of the damage. Kyle received shrapnel wounds to his face, chin, neck and right leg. In a parachute training jump Kyle got his right arm entangled in his rigging, which led to a torn tendon and debilitating tendinitis. His unit was involved in the Jessica Lynch rescue, but the mission that had the most impact on Kyle was the Ranger rescue of a Navy SEAL team on the third day of Operation Anaconda, a sweep of al Qaeda and Taliban forces in the Shahikot Valley of Eastern Afghanistan.

Although not on the mission, Kyle lost three friends on the firefight atop Takur Ghar Mountain: Rangers Marc Anderson, Bradley Crose (with whom Kyle attended paramedic school) and Mathew Commons. You can read about the harrowing battle for Roberts Ridge in Sean Naylor’s “Not A Good Day to Die, The Untold Story of Operation Anaconda” and in Malcolm MacPherson’s “Roberts Ridge, A Story Of Courage And Sacrifice On Takur Ghar Mountain, Afghanistan.” Kyle can go for days without thinking about his brother Rangers, but then something in life will remind him that they’re not here to live their lives.

Kyle would have stayed in the Army, but after seeing his parents divorce and his father remarry two more times, he knew he didn’t want to lose his wife over his career choice. He felt it wasn’t fair to Dana, so he transitioned out in 2004. Their daughter, Zoe, was born right after Kyle got out, and their son, David, was born in 2011. At first Kyle wasn’t sure what he wanted to do. He worked in an autobody shop, but when the pain in his right arm, exacerbated by a bone spur on his clavicle, got so bad he could barely function, he knew he had to find other work. “On my last day, the pain was so bad I couldn’t hold a hammer—I couldn’t hold a toothbrush.” He taped the hammer to his forearm and at the end of the day told his boss that he just couldn’t do the work anymore.

He was at the right place at the right time to land a job as an IT (information technology) contractor for Lowe’s, developing three data centers, one in Texas and two in North Carolina. When Kyle applied for full-time employment, the company told him it could not hire him because he lacked a degree. So, he went back to school. His mother was a teacher, so education has always been important to him. In the end, “100 percent and then some” in keeping with the Ranger creed, he came away with three doctorates, two in education and one in psychology.

During this time Kyle was an administrator to a local college, a school principal and eventually an acting superintendent. His frustration grew as he continually tried to hold students and parents to high standards. Kyle ensured that the children had what they needed to succeed, but if they didn’t follow the rules, they faced the consequences. He felt undermined, however, by a politically-correct environment in which his decisions were often overturned. Eventually, he just quit.

When Kyle was a school administrator, his chief financial officer asked him to make a knife he could give to his future brother-in-law as a wedding gift. Kyle was reconnected with that kid who had became engrossed in making the best knife he could make. “I enjoyed the process,” Kyle said. He began making knives “as a hobby.” Although he may not have recognized it at the time, that sounds like too casual an approach for a craft that would end up tying his love of knifemaking, education, psychology and his warrior brethren together, giving him a new mission in life.

In 2013 Nate Bocker began Resilience Forge in Virginia. Nate served in the Army with the 249th Engineer Battalion. The active-duty sergeant sought a way to help the wounded warrior community. He thought by teaching veterans the skill of bladesmithing they could hammer out some of the issues associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, receive appropriate physical therapy for some injuries and have the foundation of a new skill they could expand into a trade if they so chose. Nate’s first student christened the program Blade Therapy. Kyle then launched Resilience Forge North Carolina and began implementing standard operating procedures so that the non-profit could expand nationally. No matter where a veteran attended, they’d know that the program would be the same.

The irony is that there is no structure to the program. Veterans when they’re transitioning from active duty or medical care into civilian life don’t have a schedule. “My door is always open,” Kyle said. All a veteran has to do is call ahead and he is there to provide counselling in the active environment of the forge. “Sitting on a couch and talking doesn’t work with the military mindset. They want to be producing something,” he said. Lots can unfold in the course of making a knife in one of Kyle’s classes. Take the 96-year-old veteran who was on Omaha Beach on the D-Day Invasion of Normandy. “He couldn’t do much,” Kyle said, but it was only a couple of weeks after visiting Resilience Forge that the veteran’s wife called. “She said, ‘I don’t know what you did, but my husband is happier.’ He had opened up to her,” Kyle said. And now Kyle is happy too. He’s found his new mission.

He knows what it’s like to reach that point where it’s darkest. Where the trudging goes on incessantly, you feel miserable physically and mentally, you’re exhausted and there’s no clear purpose to your life. Irrespective of his constant advancements career-wise, Kyle knows the heartbreak of remembering lost buddies. Anderson had been a school teacher. “We all face it,” Kyle said. At one point the emotional and physical pain was so bad that he walked away from the one thing that could have ever compelled him to leave the Army: his marriage. That lasted six months. There is a point, even in knifemaking, when the challenges seem to go on for too long, when things don’t fall naturally into place, when braking the blade seems nobler than letting it crack under stress.

Kyle taps into each veteran’s ability to adapt and overcome. Even though he’s teaching a physical skill, he’s giving veterans back their confidence, their ability to overcome and adapt. He helps them find their flexibility, their resiliency, their ability to fight back and achieve self-sustainability again. He can’t tell the veteran what his new mission is, but he can guide and support him while he figures it out. And that knife that they thought they couldn’t finish becomes a token of what they’re capable of accomplishing.

DoD News In Focus: Taking The Edge Off

Kyle’s plans, not surprisingly, are big. He currently puts veterans up in area hotels. He’d like to get a camper that he could use to haul a mobile forge to VA hospitals. He could use it for sleeping on those trips and to accommodate veterans when they’re at Resilience Forge. The VA is now sending patients to him. He sees the program expanding across the country, and eventually, Dana leaving her insurance agent job and working with him. He hints at perhaps another doctorate, and in 2018 he’ll be testing for his American Bladesmith Society master smith rating in Kansas. He uses a power hammer when he’s forging his own knives, but he teaches by hand. He’s hoping to stave off another tendinitis surgery, but he can feel his tendinitis getting worse. Like many veterans, his battle for coverage continues. Even so, his mission is crystal clear, and he is happier than he’s ever been.

Donations And Inquiries

To make a donation to Resilience Forge North Carolina, you can access gahaganknives.com through Paypal, or you can mail a check made out to Joy To The World Foundation to Kyle at the address below. The Joy To The World Foundation provides administrative services, such as tax preparation, to non-profits.